What To Keep In Mind When Filing Your Business as an S-corp

Huyen Nguyen, CFP®

9/10/20253 min read

One of the big questions entrepreneurs face is how to pay themselves in a way that is both smart and responsible. It isn’t simply a matter of withdrawing money from the business; it requires an understanding of taxes, IRS expectations, and the balance between what the business can sustain and what you personally need.

Besides regular income tax, which runs through the familiar tax brackets, business owners must also deal with self-employment tax. This tax totals 15.3 percent, broken into 12.4 percent for Social Security and 2.9 percent for Medicare. Because self-employed individuals act as both employer and employee, they shoulder the full burden of these taxes, which can be a heavy expense.

For that reason, many high-earning business owners, particularly those with net income above $150,000, choose to elect S-corporation status. Filing as an S-corp changes the way the IRS views the business. Instead of being taxed purely as self-employed, the owner becomes both an employee and a shareholder. The business can pay the owner a moderate and reasonable salary as W-2 income. This salary is still subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes, but at only half the full rate since employees pay one half while employers cover the other. The business, in turn, pays the employer’s share along with unemployment insurance premiums. Any profit left after salary can be distributed as a dividend. These dividends are taxed as ordinary income but escape the additional 15.3 percent self-employment tax, which creates meaningful savings for owners of profitable businesses.

Electing S-corp status does mean additional paperwork. The IRS requires Form 2553 for an LLC or C-corp to be taxed as an S-corp, and Form 8832 is used when a business changes its taxable status. An S-corp must also file Form 1120-S each year to report income and taxes. Payroll taxes come into play too, including federal, state, and local withholdings, along with the employer’s portion of Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment taxes. Self-employment taxes remain a burden for sole proprietors or disregarded entities, but an S-corp offers a way to reduce that load. The Qualified Business Income deduction, another benefit, begins to phase out at $197,300 for individuals and $394,600 for married couples filing jointly in 2025. Owners must also be cautious when converting back from a corporation to an LLC or partnership, since the IRS may treat that as liquidation and apply capital gains taxes.

Understanding how different structures work is important when deciding how to pay yourself. A C-corporation, for example, comes with double taxation but allows for international recognition, multiple share classes, and access to a broader investor base. It also requires stricter record-keeping. An S-corporation avoids double taxation by passing income through to shareholders and offers savings on self-employment taxes, though it is limited to domestic operations, one share class, and 100 shareholders. In practice, most small businesses begin as LLCs and then elect S-corp status to gain the tax advantages without taking on the full complexity of a traditional corporation.

The next question is how much you should actually pay yourself. The IRS doesn’t define “reasonable salary” with precision, but it does expect owners to pay themselves what someone else in the same role and with the same responsibilities would earn on the open market. Salary is a deductible business expense, and while paying yourself a low salary can reduce Social Security and Medicare taxes, it may increase your overall income tax burden and, worse, expose you to penalties. If the IRS decides your salary is unreasonably low, you could face fines equal to 20 percent of the underpayment. Consistency and fairness are the best guides here.

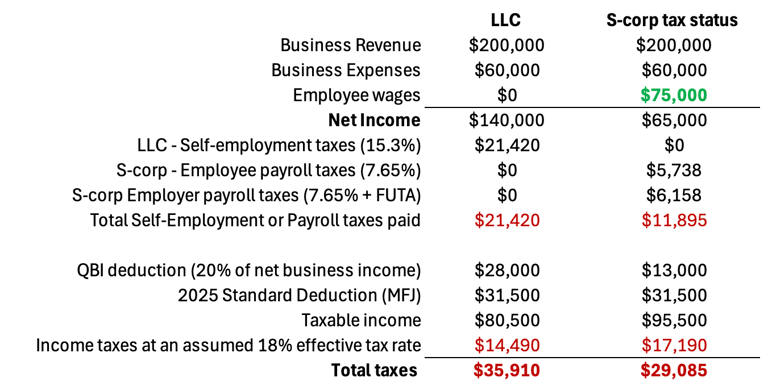

Here is a simplified example comparing the total tax paid between an LLC and an S-corp:

** FUTA (Federal Unemployment Tax Act) includes 6% on the first $7,000 salary

It is also worth clarifying the difference between a salary and an owner’s draw. An owner’s draw is when the business owner takes money directly from business profits for personal use. This is common in sole proprietorships, partnerships, and some LLCs, but it is not allowed for S-corporations or C-corporations. Draws are not taxed until they exceed the owner’s original contribution to the business, at which point they become taxable as profit. By contrast, S-corp and C-corp owners must take compensation either as salary or dividends.

There are also common mistakes to avoid. Some owners underpay themselves, thinking it will save money, but this risks IRS scrutiny and penalties. Others fail to track draws or forget to withhold payroll taxes, which can create a mess at tax time. Skipping quarterly estimated tax payments or mixing personal and business accounts are other missteps that can complicate both your books and your relationship with the IRS.

In the end, paying yourself as a business owner requires careful planning. For many, the most efficient route is to operate as an LLC taxed as an S-corp, combining reasonable salary with dividend distributions to reduce self-employment taxes. No matter what structure you choose, though, the essentials remain the same: pay yourself fairly, stay consistent, and keep meticulous records. Doing so protects both you and your business and sets you up for long-term success.

Inclusive Wealth Financial Planning LLC is a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA) registered in Pennsylvania and Texas. We may also serve clients in all other states pursuant to the de minimis exemption.

Verify CFP | SEC Investment Adviser Public Disclosure

ADV Part 2A &2B | Privacy Policy | Term of Use (Kindly be advised that upon clicking, these files will be downloaded to your computer.)